This article first appeared in Quadangles on March 14, 2018

After a childhood scarred by addiction, Jim Prochaska has dedicated his life to figuring out how people can change for the better. Interventions based on his theories—which remain some of the most widely cited works in psychology—have helped therapists around the world assist patients with problems like giving up smoking, improving diet and exercise, and breaking addictions to alcohol and drugs. At 75, he’s still teaching, and still changing lives.

By Paul Kandarian

James O. Prochaska grew up in Dearborn, Michigan, a suburb of Detroit, in the 1940s and 1950s, surrounded by automobile factories. It was, he says, a place to “appreciate the wisdom of ordinary people,” such as seamstresses, mechanics, barbers, and cooks.

His mom was a part-time waitress, his dad a worker on an assembly line. His father was also, sadly, a man Prochaska would watch slowly succumb to alcoholism.

“I often felt helpless, and I hate feeling helpless,” says Prochaska, now 75, director of the University of Rhode Island’s Cancer Prevention Research Center and a long time professor of psychology. “When my father was good, he was wonderful. When he was bad, he was very, very bad. He had a number of demons, including violence, alcoholism, and being bipolar

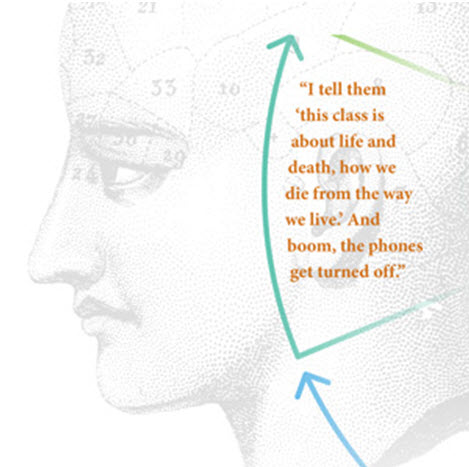

It was that feeling of helplessness that prompted him to pursue a career in psychology, one that would include creating a revolutionary model for the decision-making that allows people to implement positive change. Called the Transtheoretical, or Stages of Change, model, it was born in the 1970s from studies that examined why some smokers were able to quit, while others failed. Since then, Prochaska has developed applications to health-related behaviors—smoking, diet, exercise, and safe-sex practices—and to mental health-related problems, such as alcohol and drug abuse, stress and distress. He also developed interventions that can help accelerate changes in problem behaviors, as well an integrative model of psychotherapy.

It was that feeling of helplessness that prompted him to pursue a career in psychology, one that would include creating a revolutionary model for the decision-making that allows people to implement positive change. Called the Transtheoretical, or Stages of Change, model, it was born in the 1970s from studies that examined why some smokers were able to quit, while others failed. Since then, Prochaska has developed applications to health-related behaviors—smoking, diet, exercise, and safe-sex practices—and to mental health-related problems, such as alcohol and drug abuse, stress and distress. He also developed interventions that can help accelerate changes in problem behaviors, as well an integrative model of psychotherapy.

Along the way, he has earned a raft of awards, including being named one of the Top Five Most Cited Authors in Psychology from the Association for Psychological Science, an Innovator’s Award from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, and a Medal of Honor for Clinical Research from the American Cancer Society—the first psychologist to win one. It’s no exaggeration to say that he’s a giant in the field, and that his work has had a profound effect on thousands of lives. To that end, Prochaska also founded, with his wife Janice, a company called Pro-Change Behavior Systems in 1998. He sums it all up by saying he and his wife “continue with our mission of enhancing the health and happiness of as many people as possible.”

Among the lives he has touched are hundreds of students. “He’s an incredible mentor, a brilliant man, prolific writer and a role model for countless students,” says one former student, Sara Johnson, M.S. ’95, Ph.D. ’98, who is now CEO and president of Pro-Change Behavior Systems after buying the company from the Prochaskas in 2015. “He is the reason I chose URI for graduate school.”

But as his adult life was getting started, with his difficult childhood still fresh, Prochaska experienced what he calls “a series of false starts.” He’d played football at Fordson High School in Dearborn, where he met Janice, then a majorette, in the band room of the school. He played football in college as well, and initially thought he would become a minister. But the Presbyterian college he had won a scholarship to attend, Muskingum College in Ohio, wasn’t a good fit. “I didn’t realize how conservative it was,” Prochaska says. “We had 2,000 students; 30 of us were for John F. Kennedy and the rest were for Nixon.”

But as his adult life was getting started, with his difficult childhood still fresh, Prochaska experienced what he calls “a series of false starts.” He’d played football at Fordson High School in Dearborn, where he met Janice, then a majorette, in the band room of the school. He played football in college as well, and initially thought he would become a minister. But the Presbyterian college he had won a scholarship to attend, Muskingum College in Ohio, wasn’t a good fit. “I didn’t realize how conservative it was,” Prochaska says. “We had 2,000 students; 30 of us were for John F. Kennedy and the rest were for Nixon.”

He dropped out to travel with migrant workers, writing a column about the experience called “Bohemian by Birth.” A couple of years later, still deep in the grip of counterculture, he realized he wanted to go back to college. Ohio State had its allure—but at a dinner where legendary Buckeyes coach Woody Hayes was holding court, he heard the coach say he’d have “no long hairs on his team.” Prochaska remembers that, “Everyone just looked at me, and that was that.”

So he ended up at Wayne State University, a public-research facility back in Michigan that Prochaska describes as being, at the time, “known as a Communist college.” It suited his needs; he’d also go to Clark University and the Merrill-Palmer Institute, but Wayne State is where Prochaska earned his bachelor’s degree in 1964, his master’s in 1967, and his Ph.D. in 1969.

The deep dive required by so much study in psychology changed him. “I went into therapy at Wayne State,” he remembers. “It was a requisite at the time, but I was battling with my own depression. Being in therapy was part of getting your Ph.D., and I wish we still did that. It’s a great way to get a deeper sense of ourselves.”

He was afflicted with self doubt. In his stint in therapy, he says, “I remember telling my therapist I should have gone to Harvard, that I’d never do anything great at a state school. He looked at me and asked, ‘Why not?’ ”

The question, or perhaps challenge, stuck with him, guiding him over the years. It’s message, he came to believe, was that you could find whatever you need inside yourself—you didn’t need to wait for it to come from the outside.

“That’s a message I still share with my students,” Prochaska says. “You can go to a state university and do great things. Why not?”

He and Jan married in 1966, and after he got his Ph.D., he started looking at places outside of his Midwest comfort zone.

“I didn’t know about URI, so I came and interviewed,” he says. “They were starting a Ph.D. program. It seemed such a welcoming atmosphere, and Jan and I both loved it. I thought as new faculty, I could impact the school’s new Ph.D. program.”

After he had won tenure, and had a family and a place in the woods and what should have been feelings of security and happiness, the familiar shroud of depression reared its ugly head once more. He told himself he should have gone to Penn State to do great things. But then the therapist’s voice from the past returned, and he asked himself why he couldn’t do great things right here.

“That was a crisis point in my life,” he says. “I was reading a philosophy of science book that said the best science is done by those passionate about their work, and I was passionate about personal freedom and saw this as freedom to change my own behavior. I threw myself into that, and the rest followed.”

What followed was the origination of The Transtheoretical Model (TTM) of behavior change, an integrative theory of therapy that assesses an individual’s readiness to act on a proposed new behavior, and provides strategies to help implement the change. It is a roadmap for moving through what Prochaska and his fellow researchers identified as the five stages of behavior change: precontemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, and maintenance.

Its international adoption is doubtless in part because it can be applied to so many areas of life. After all, as health researchers know so well, many major illnesses—cancer, diabetes, and heart disease, to name a few—result from preventable behaviors: smoking, bad diet, and inactivity.

The model is only one part of a storied career. While at URI, Prochaska has served as principal investigator on more than $80 million in research grants on the prevention of cancer and other chronic diseases, authored more than 400 publications on behavior change for health promotion and disease prevention, and published four books on change, including the most recent, Changing to Thrive, with his wife in 2016.

“The University and country are fortunate he chose the profession he did,” says Johnson, CEO of Pro-Change Behavior Systems, now an adjunct faculty member in URI’s psychology department. “He’s not pretentious at all, and genuinely cares about enhancing health and well-being for everyone.”

“One thing I think of in knowing him is that it must be great going to sleep at night knowing you’ve done things to change the behavior of hundreds of thousands of people that’s made their lives substantially better,” says David Faust, URI professor of clinical psychology. “And he’s so positive and encouraging with his students, he makes them feel excited and inspired.”

One such student is Luke Daniels, 25, who is in URI’s Ph.D. program in clinical psychology and came to the university specifically to be mentored by Prochaska.

“We bounce ideas off each other—and that’s amazing to me, bouncing ideas off Dr. Jim Prochaska,” Daniels says. “Working on studying health behaviors with him is like studying DNA with Crick and Watson.”

The latest challenge, and opportunity, for Prochaska and his colleagues is that URI’s new Academic Health Collaborative is bringing together a diverse assortment of disciplines all focused on human health and wellness, including the Colleges of Health Sciences, Nursing, and Pharmacy. Prochaska has helped take the lead in designing the collaborative’s Institute for Integrated Health and Innovation.

The new institute will house Prochaska’s Cancer Prevention Research Center, which he’s directed since 1989. It’s where the research “needs to be,” he says, “part of this whole new transformation. I’ve spent three years on planning committees and it’s all led us to making a terrific plan a reality. I want to contribute and be confident things are functioning the best they can.”

At 75, he has no plans to quit soon, saying “I wouldn’t retire anyway; I’d repurpose.” The most important thing, he says, is continuing his mission. “The cancer research and the Academic Health Collaborative and the new institute, it’s all about enhancing health and well-being for as many people as we possibly can,” Prochaska says. “It’s still very exciting and rewarding.”

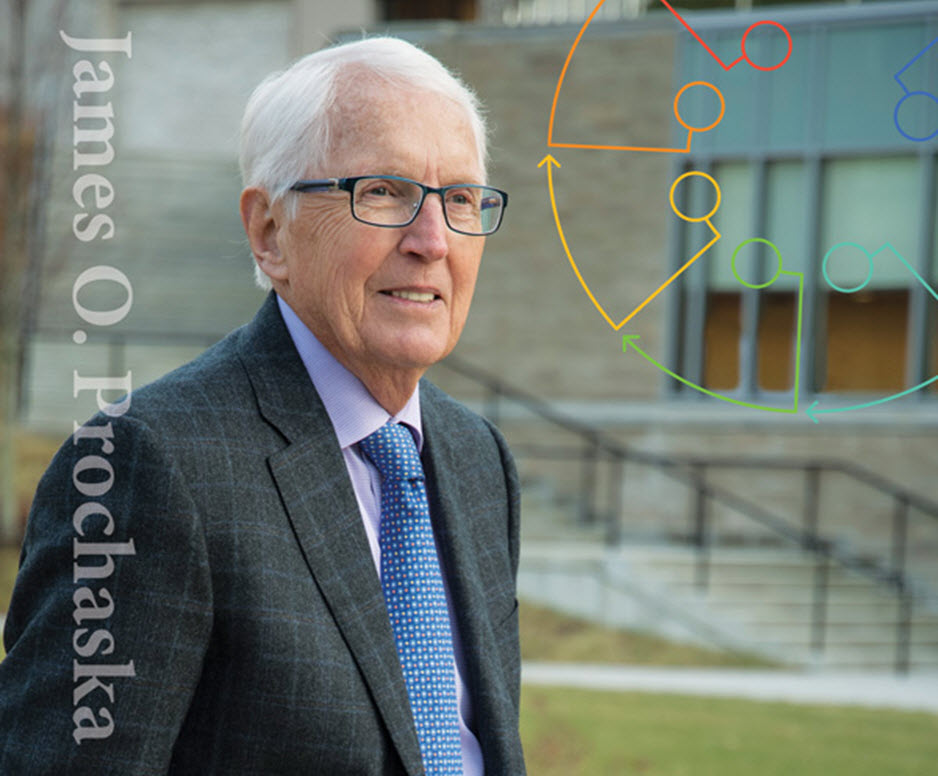

Most of all, he lights up when he talks about his work as a teacher. Yes, it can be a challenge to get modern students to look up from their smartphones, but as usual, Jim Prochaska has a strategy. “I tell them, ‘This class is about life and death, about how we die from the way we live,’” he says. “And boom, the phones get turned off.”

Professor Prochaska invites readers to a Sept. 13 event at which he’ll present stories and discoveries from his work, particularly at the Cancer Prevention Research Center, that produce unprecedented impacts on people’s health and well-being.

More info: uri.edu/research/cprc.